Sensorial Superpowers

Young children are in a powerful process of creating an understanding of their world and where they fit in. To do this, they rely upon their senses as an interface to the world. Everything that comes into young children’s minds comes through their senses.

During the first few years of life, children are absorbing sensory input without any discrimination. Then around age two-and-a-half to age three, children begin to bring images from their subconscious into their consciousness. They begin to work with these images and in the process embark on an important journey of building their intelligence.

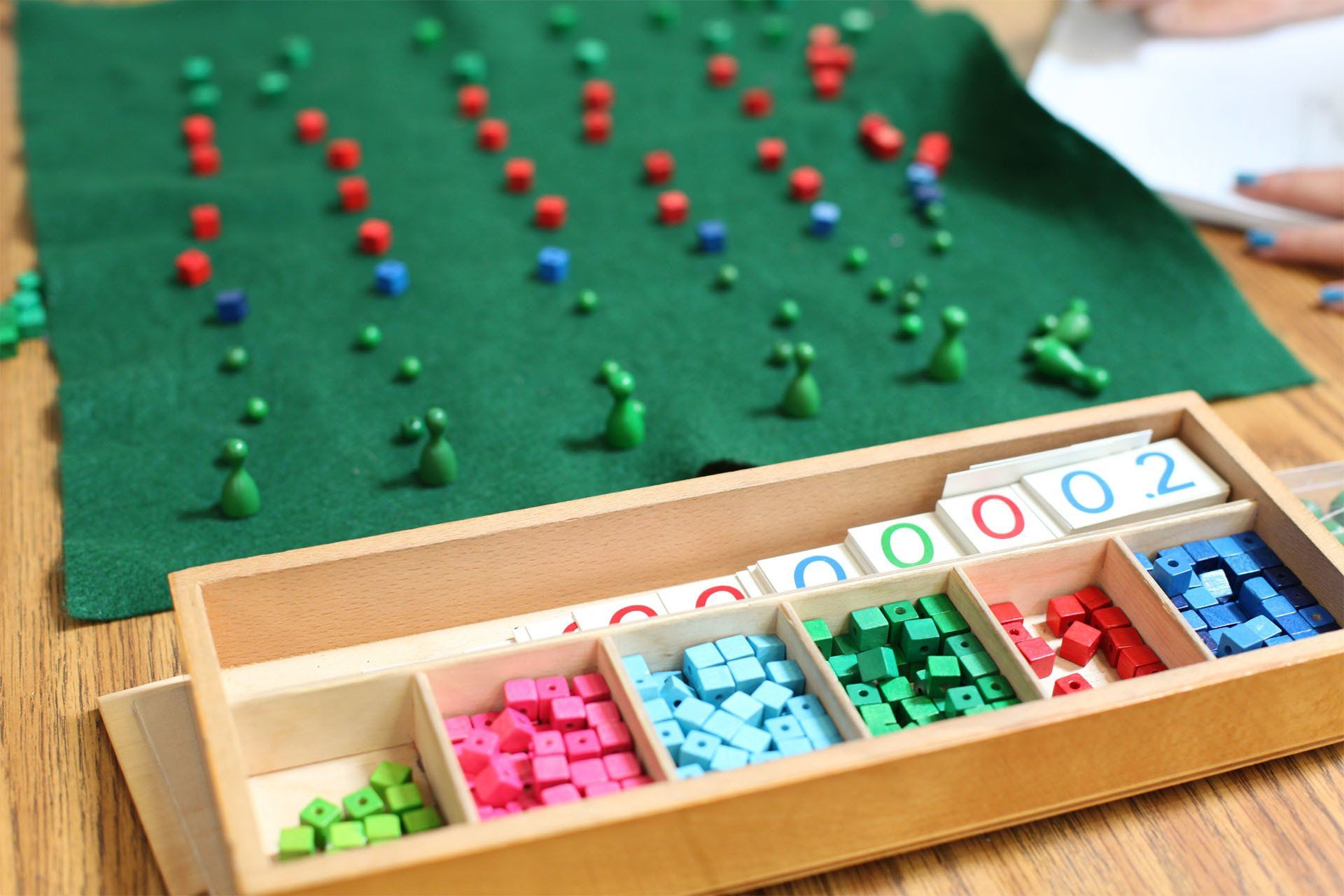

The Sensorial Materials

To support this development, Montessori programs offer carefully designed sensorial materials.

that follow a formal, systematic approach. The materials isolate each sensorial quality and offer children what Dr. Maria Montessori called the “keys to the world.” In addition, the sensorial materials support children’s classification of impressions and lead to clear levels of conscious discrimination. If children have these experiences in the formative period of brain development, they establish a foundation for a lifetime of order and precision, as well as logical, reasoned thinking.

How do sensorial materials accomplish all of this? Well, they have some really significant purposes!

Sensorial materials support children’s classification and categorization of sensorial impressions.

For young children, the first three years are like collecting impressions and throwing them into a closet. The images or concepts are a bit of a hodge-podge jumble, thus to go in and access what is needed from this unorganized collection can be a challenge. Because this warehouse of impressions doesn’t have order or classification, children need to develop mental organization so their collection of impressions becomes useful.

The sensorial materials help children to classify and categorize all of the impressions they have absorbed and unconsciously stored since birth. When children interact with the sensorial materials, images come out of their unconscious memory and come into working memory. As children use the materials, these impressions become part of their conscious memory. When children become accurate in distinguishing sensorial differences, we give language for the images, which then helps the concepts become fixed in children’s minds.

Children aren’t born with organized brains that have predetermined categories, so this neural organization has to be built up through experience.

Sensorial materials support children’s refinement of their sensorial perceptions.

It’s important to understand that sensorial exercises don’t make children’s ears hear better, eyes see better, or tongue taste better. Rather, the materials help children develop powers of discrimination so that they can analyze smaller and smaller degrees of difference.

When we take in sensorial input, everything goes into our brain. Then the brain has to make discriminations, a skill which develops through experience and the process of making finer and finer discernments. The materials offer children a clear means for starting to classify and to increase their perceptive powers, both of which are important mental abilities.

Sensorial materials support children in the development of abstractions.

What do we mean by abstractions? An example of an abstraction is the notion of “red.” Red as a quality does not exist in nature. Red can be represented in physical things, but we cannot bring “red” to a person. Red is a quality. It is an abstraction.

Children may have some abstractions already in place, but when they are young the number is limited purely due to the fact that they haven’t had a sufficient amount of experience to develop the abstraction. Furthermore, children don’t typically get to experience sensorial qualities in isolation. The Montessori sensorial materials isolate each quality and give children the opportunity to have enough experience to develop abstractions.

Because we, as adults, have a lot of experience in the world, it can be hard for us to understand what children need to create abstractions. To better understand the significance of abstractions, imagine being told about a quince. If you haven’t had a quince before, it is hard to pull up the image in your mind, much less what it tastes like. If you hear a description that a quince is a fruit, you are able to pull up an idea of what a fruit is. Then if you hear that a quince is in the same family as an apple and pear, you can pull up an image that brings you closer to imagining the fruit and perhaps even the type of skin it has.

But without these experiences and the organization of images, children can’t pull up the same level of abstraction. Imagination helps us, as adults, to be able to do this: pull up images in our minds of something haven’t experienced before based on abstractions. In order to imagine, we must have abstractions. This area is most related to the development of intelligence.

Sensorial materials support children’s development of accurate and discriminating recall of perceptions.

The materials engage children’s memory, help them access information from their memory, and support them in using their intelligence. Memory is a tool of the intelligence, but because children aren’t born with memory, they need support with developing it. While children do have an unconscious memory, they have to take the impressions they have absorbed and build memory from them. The sensorial materials help this process.

Memory needs practice and experience to become stronger; it is only increased through activity. We want children’s memory to be strong and thus we provide lots of experience with the materials and variations with the materials. With each sensorial material, there are many ways to extend the activity and help children with recall.

One significant strategy is giving language to each perception. The language is based on what is isolated in the materials–thick/thin, large/small, long/short, right-angled isosceles triangle/right-angled scale triangle, rough/smooth, heavy/light, ovoid/ellipsoid, bitter/sweet. The vocabulary is extensive and rich, and ultimately fixes the perception in children’s memory.

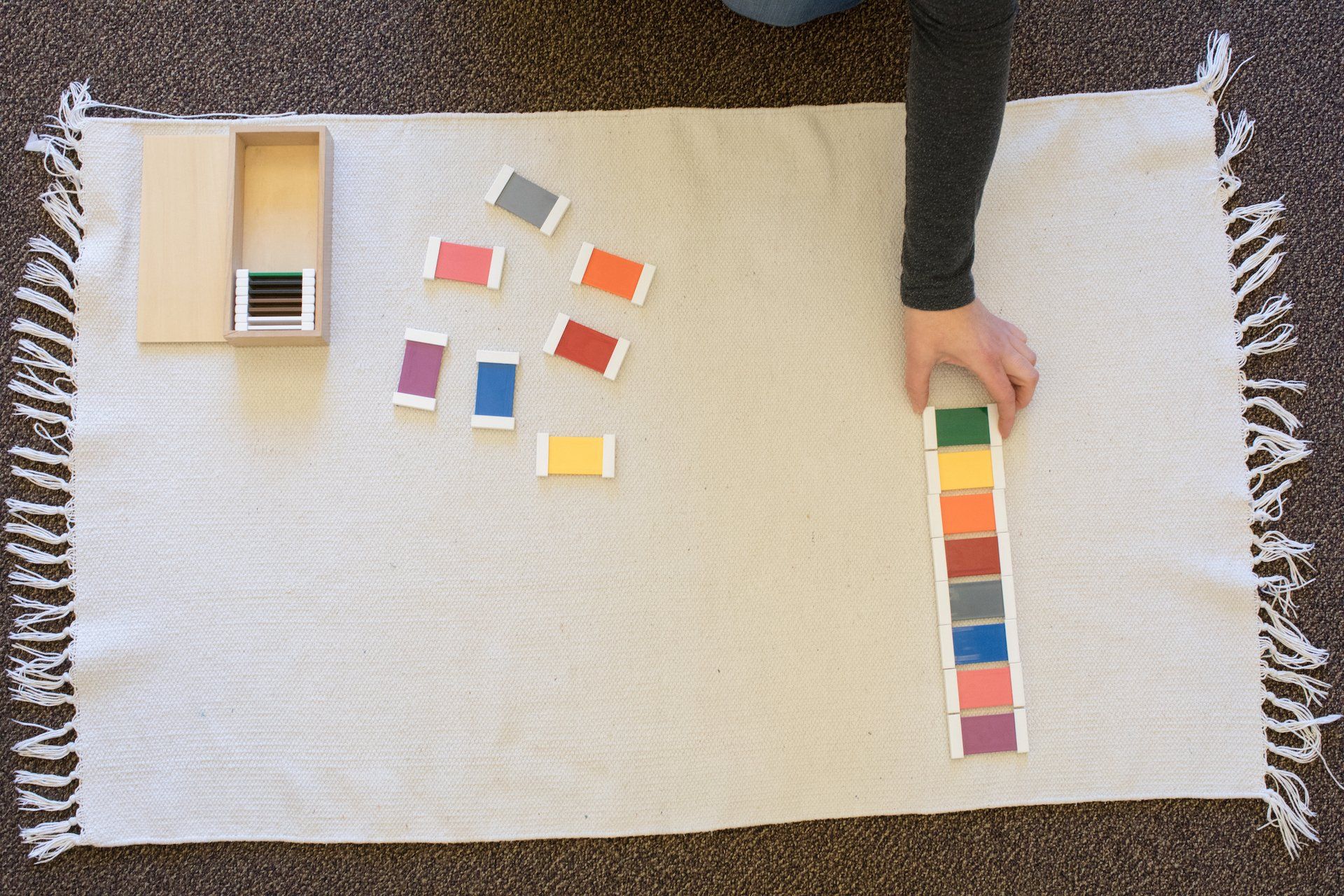

The second strategy we use is playing games which challenge children to hold the perception in mind for longer and longer periods of time. They might put each of the pink tower cubes scattered about the room so that in rebuilding the tower of cubes from largest to smallest, they have to remember the size of the previous piece in searching for the next largest cube. Some of the sensorial games also help children notice particular qualities in the environment, rather than just in the materials. One favorite is searching for items in the classroom that have exactly the same shade of each of the color tablets.

Through repeated experience with the sensorial materials, children develop clearer and more accurate perceptions and create reference points that they can use throughout life. Dr. Montessori talks about the possibility for children to develop touchstones, a sort of fixed, accurate reference by which this quality can be accessed. These points of reference can provide a lifetime tendency for order, precision, and recall, for example hearing the note of G without any other reference or being able to look at a pane of glass and know if it will fit into the window frame.

Sensorial materials help children develop life-long tendencies towards order and precision.

We don’t know what touchstones might develop for each child, but Dr. Montessori says that touchstones developed during these early years will remain with children throughout their whole life. If children can get accurate discriminations while in this time of sensitivity to sensorial input, this precision will remain with them into adulthood. Of course, children’s unique interests will also lead them to their own level of proficiency.

Functionally, this tendency toward order and precision will be important as children move into more academic work in language and math. They will be able to access powers of discrimination that will aid them in future endeavors.

Sensorial materials also provide indirect preparation for further study.

This indirect preparation means that we are taking advantage of children’s spontaneous interest and activity and thus planting the seeds for other areas that children will explore as they get older. When we introduce shapes–from a decagon to an ellipse to a quatrefoil–through the geometry cabinet, children visually discriminate the shapes while also tactilely experiencing the shapes by tracing around them. Multisensory input is stronger than input through just one sense. Tracing the shape also helps to prepare children’s hands for writing. To write, our hands have to be able to follow a form. This is how the sensorial materials provide indirect preparation for further academic study.

Sensorial materials support the development of children’s memory and intelligence.

Dr. Montessori talks about the sensorial area as being most strongly related to the development of intelligence. Working with sensorial materials requires a very different engagement from the practical life work of washing hands or scrubbing a table. Practical life activities help children with coordinating movement and following a sequence with a logical beginning, middle, and end. Sensorial materials don’t have the same kind of logical sequence. They are open-ended and exploratory. Children have to consider each piece and how it works in relation to the other pieces. In working with the red rods, for example, children have to examine each rod’s length in relation to the other rods. Thus, children have to make a reasoned distinction every time they move a piece of material. This process engages the intelligence and elevates children’s level of awareness. In addition, children then have to hold the images in their mind, which helps their memory.

Having an ordered, classified mind is also the foundation for intelligence. When children struggle in more academic areas like language and math, we take time to consider how to better support their mental order and classification. When the mind isn’t prepared well, academic work can be difficult to do. However, if children can recognize and distinguish between a trapezoid and a parallelogram, they will be more likely to be able to distinguish two other shapes like “g” and “q.” When children have a lot of experience recognizing shapes through sensorial materials, they are more able to recognize the shapes they encounter in letters. Sometimes we go back and explore if perhaps children recognize the shapes but don’t have a strong memory. We then use sensorial games specifically designed to help different forms of memory (auditory, visual, etc.).

The sensorial area serves as an important foundation for more academic work because language and math are completely based on abstractions. Words represent concrete things but the words themselves are abstractions. The sensorial area is critical for providing the foundation for abstract thinking.

Outcomes

Although the sensorial materials may look relatively simple, they provide so much! When children use these materials, they are refining their powers of discrimination, creating an ordered mind, enhancing their memory and recall, categorizing their impressions, and building a foundation for rational thinking and intelligence.

As children achieve these skills, they experience life with an increased level of richness, becoming aware of the lovely details of their world. With a prepared mind, children can see things in a new light and with new enthusiasm. This is perhaps one of the most delightful outcomes of children’s work with the sensorial materials: they develop a whole new appreciation of the life around them–dimensions, shapes, smells, sounds, textures, tastes–which is what gives life value and beauty.

We hope you can come visit our school, experience the sensorial materials, and see how children get to develop their sensorial superpowers!